Hours before sunrise last Friday, an unlikely group gathered at the eastern edge of Ckuwaponakiyik, Schoodic Point. Wabanaki community members and the National Park Service welcomed world renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, and a handful of Maine’s Tribal and State representatives for a concert and conversation at daybreak.

The concert was a collaboration between Yo-Yo Ma and seven Wabanaki musicians, debuting Ma’s new project that will take him across Turtle Island to perform in natural spaces. His vision is to collaborate with and uplift Indigenous voices for healing through music, nature, and listening. Featured artists and culture keepers were: Lauren Stevens, Christopher Newell, Rolfe Richter, Lynn Mitchell, and Matt Dana representing the Passamaquoddy Tribe, Hawk Henries representing the Nipmuc Nation, and Roger Paul representing both Passamaquoddy and Wolastoqi communities.

Beginning around 4:30AM, Rolfe Richter and language keeper Roger Paul shared the story of how the Wabanaki learned to welcome the sun each day. As People of the First Light, Paul said, we have the responsibility to encourage kisos (the sun) to return by singing him a song. Yo-Yo Ma joined the musicians as kisos broke over the horizon.

Executive Director of the Abbe Museum Chris Newell reflected that, in organizing the event, “Yo-Yo and [his team] always put Yo-Yo as a Guest in Wabanaki homeland.” The attitude was, “this is Wabanaki land, therefore I’m a guest… He gave the power over to us to create the performance that would be meaningful to Wabanaki people, and he was a willing participant.” Roger Paul explained further, “This all stemmed from Yo-Yo Ma’s heart. He had gone through the pandemic and seen all the problems of racial injustice […] and how the country has come apart at the seams. They wanted to be able to hold an event to draw people together that could help the world heal.”

While the concert was originally planned for an audience of Wabanaki community members and invited guests, it ended up drawing in several state politicians. “Initially it was not supposed to be all political leadership,“ said Newell. In addition to Haaland and Tribal representatives, State Governor Janet Mills, U.S. Representatives Chellie Pingree and Jared Golden, and Senator Angus King were in attendance.

Adjusting to the new audience, Wabanaki people used the opportunity to host a talking circle and address ongoing issues including Sovereignty, language preservation, and land return. The tradition is a key part of Wabanaki culture and governance. It is an equalizing practice where everyone is allowed to speak about whatever they need, for as long as it takes. The circle teaches our youth to speak confidently, openly, and from the heart when addressing the community. Equally important, it teaches patience and attentive listening. The talking circle carries forward core Wabanaki values of reciprocal respect, integrity, honesty, and equality.

During the two hour circle, Wabanaki people spoke of the importance of our language and our elders, who together hold the knowledge of how to govern these homelands sustainably. They recognized our ancestors who kept this land healthy for over 12,000 years, and the short 200 years of Maine statehood that is swiftly desecrating it. They spoke about the sovereignty bills now in Maine’s legislature that would enable us to protect our homelands as we have always done. Governor Mills has consistently fought against Tribal Sovereignty, so she was invited into the circle to share or to correct anything she felt was misstated. She declined, and later fell asleep.

Mills was not personally invited to the concert, but got word of it the day before. Many wondered why she was there if she did not want to speak with us, and some felt that she was merely there for the photo-opportunity. Wabanaki people and representatives nonetheless used the chance to speak to her directly.

Bridgid Neptune (Passamaquoddy) and ally Fiona Hopper addressed Mills about improving Wabanaki Studies in public schools, which is required by Maine State Law LD 291. Despite the requirement passed in 2001, says Neptune, “LD 291 is not implemented because districts have weak budgets and are expected to develop and include Wabanaki Studies without any funding from the state.” Neptune and Hopper, with guidance from Tribal leaders and thought-partners are developing a curriculum for Portland Public Schools that would provide training and materials for preK-12 classrooms and be a model for schools statewide. “Teachers really need guidance [to teach Wabanaki studies], and need to be held to some particular standards,” says Hopper. They are trying to fundraise $100,000 for the program, but Governor Mills left the conversation when asked if the State might provide financial support to implement LD 291.

Tribal leaders met with Interior Secretary Haaland on Thursday before the event to discuss several upcoming Sovereignty bills: LD 1665, LD 1626, and LD 159. The bills seek to correct injustices created by the 1980 Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act (MICSA), whose language classifying Tribes as “municipalities” stripped them of many Sovereign rights. Maine’s legal maneuvering in 1980 was explicitly intended to keep tribes under State jurisdiction, unlike all other Federally Recognized Tribes who entirely bypass State law to fall under Tribal and Federal Jurisdiction, as guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. From an internal document written to U.S. Senator Bill Cohen by Tim Woodcock, who served as minority staff counsel on the Senate Select Committee on Indian Affairs and was actively involved in the drafting and enactment of the 1980 Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act. This letter was not shared with the Tribes.

“The municipality concept was adopted because it was believed to be the best device to ensure that the Tribes remained under Maine law and did not take on the substantial attributes of sovereignty, which characterize many of the Tribes in the West. The State believed that it was avoiding the creation of a Nation within a Nation, which Governor Longley had vigorously decried. The best device to ensure that the Tribes remain under Maine law and did not take on the substantial attributes of sovereignty,” (letter from Tim Woodcock to Senator William Cohen in August 1980, supplied to Sunlight Media Collective by Representative Jeffrey Evangelos of House District 91

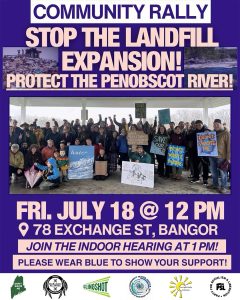

States tend to fight hard against Tribal Sovereignty because it’s one of the only mechanisms that can legally bind the actions of the State. For example, recognizing Tribal Sovereignty over the Penobscot River (which is named in treaties as part of the Penobscot Reservation) would not be favorable for the State, because Maine is drawing large profits from dumping chemical waste leachate in the Penobscot through arrangements with Juniper Ridge Landfill and Old Town’s ND Paper mill.

Passamaquoddy lawyer Corey Hinton said the meeting with Secretary Haaland went very well, and reflected, “She gets it, and she can advocate for our Tribal sovereignty in Congress, which is what we need.”

Haaland also thanked Tribal leaders “who haven’t given up yet” despite “the tone in this country that sometimes feels unbearable.” She said to the circle, “we can’t ever give up. We have to keep working because our people are relying on us to keep that path open.”

“It’s not perfect, but we have to work together to be good stewards of the land” echoed Passamaquoddy Chief Maggie Dana of Sipayik. “We try to go to the table and work with the state… we keep going back. It hasn’t been favorable for us but we just keep working at it […] We’re building relations, which is just what I believe in I guess.”

The idea of ‘building relations’ permeated the event, and is built into Yo-Yo Ma’s vision for the performance series. Wabanaki people have been trying to establish mutual respect, peace and sustainability with Euro-Americans in our land for 500 years, and many feel that now is our last chance. It is required to heal racial and environmental injustices and ensure a future for generations to come.

“There are a lot of important people in this space today who can make change happen for our people,” said Lynn Mitchell of Sipayik, addressing politicians in attendance. “My friend Maria Girouard [Penobscot] says, ‘the history needs to be told and heard with compassionate ears.’ That is true, but now we need to step a little bit further and make things happen. Things that were taken away from us a long time ago. And you have the power to do that. A lot of people here.”

Mitchell’s statement resounded throughout the circle. “The land, language, healing… it all connects,” said Chief Maggie Dana. “I wasn’t brought up as a speaker but it was in my house… and as you get older, you start to wonder ‘why wasn’t I taught?’”

The theft of both land and language through colonization is intrinsically connected. “The owner’s manual of how to live sustainably in the land is in that language that you heard spoken [today], because that language was passed down from people where the land taught them how to speak,” said Chris Newell. “We have a purpose here, and you as non-natives here have a purpose as well […] It’s important for us – not just as Wabanaki but as human beings altogether to realize our collective responsibility to this place that we all reside in, that we need to keep alive.”

After the circle, Passamaquoddy Representative Rena Newell and Chief Dana both reflected on the idea of having a seat at the “rectangular” table of American politics, and the “circular” table of Indigenous community. “I’ve spent so many years earning the credentials required to gain a seat at their table,” Newell said, referring to Maine’s legislature. She confessed that having a seat among Maine’s powerful people doesn’t guarantee that you will be heard. There has to be respect and a willingness to listen and be in right relation.

There were many important words spoken that morning for those willing to hear. The talking circle ended with allies vowing solidarity, calling for accountability, and committing to change-making. “As a non-native person I feel a tremendous amount of responsibility to do right as a Wabanaki studies coordinator. It’s not a given that education is used for good,” said Fiona Hopper. Members of the National Park Service spoke of collaborating with Tribes. Founder of Indigo Arts Alliance Marcia Minter said, “I’m grateful to be here today honoring your ancestors, who are also my ancestors, who are our ancestors of this land… I very implicitly and specifically wanted to [be here to] represent the African American communities of the United States and our solidarity with the Indigenous Peoples of this land.”

Wabanaki youth humbly thanked the elders who kept Wabanaki traditions, ceremonies and languages alive even when it was scary and dangerous. “Even when it was illegal to do so,” said Sipsis Peciptaq Elamoqessik of Modahkmikuk. Bonnie Newsom of Penobscot Nation said, “this land is here because of our ancestors’ good decisions. The last 500 years we’re struggling because of poor decisions […] Being in this space in these kinds of events and coming across cultures is our way forward to heal.”

Closing the talking circle, Roger Paul challenged the audience to “stop thinking in English.” He said, “When you pick up a handful of soil, you’re holding the molecules of our ancestors, the nutrients that create new life for future generations. All of us come from her, our mother. The sunlight meeting the earth causing nutrients for us to grow, to eat. Those trees, that grass, all the animals, are part of the same creation made by the sunlight and the earth that creates life. That’s what you need to be thankful for […] When we talk about Land Back, we’re talking about Sovereignty back to Her,” he said, pointing at the Earth. “She tells us what she needs, we respond.”

Chris Newell was optimistic after the event, saying “I think we moved the needle a little bit with some of these people on their thinking about how to govern this land. That it’s not all about converting and developing things to make money, or [economic growth], and that conservation is not just putting things in a box or just allowing things to grow wildly. You know, human beings actually have a role in [this ecosystem], and it comes from our Indigenous culture. The blueprint of how to take care of this land sustainably, 12,000 years worth of knowledge, is located in our language.