A Report on the Skutik – St. Croix River

Statement of Cooperation Signing Ceremony

by Dawn Neptune Adams, with Sunlight Media Collective, June 2022.

The Skutik River watershed has always been home to the Peskotomuhkati people.

The River, renamed the St. Croix by colonial settlers, has suffered from years of human interference and abuse, including dams, industrial pollution, and the state-mandated closing of fish passageways in 1995, all resulting in the decimation of water quality in the Skutik watershed and mass depletion of fish populations. Chief Maggie Dana of Sipayik said, “When I think of the condition of the Skutik River, I think of the direct relation of colonialism and its systems. There’s been years of destruction and pollution, profit-making, and as a result, this is what you see.”

Colonial settlers built dams on the River to power industrialization in Passamaquoddy territory. They constructed most of the early wing dams on only one side of the River, with a passageway for timber. These dams allowed passage of migrating sea-run fish to the furthest reaches of the watershed when the lumber chutes were unobstructed by cut trees. In 1825 the Union Mill Dam was built at Siqoniw Utensehsis, the head of the tide and a village of the Passamaquoddy people, located at what is now called Calais, Maine, and Milltown, New Brunswick. This river impediment stretched from shore to shore and was the first to block fish from their ancestral waters upriver. Throughout the 1800s and 1900s, industry and municipalities used the Skutik River to dispose of toxic industrial waste and untreated sewage. It was blocked or partially blocked by six major dams, with additional smaller barriers blocking upstream habitats. Cotton and textile mills, paper mills, sawmills, and tanneries littered the riverbed with debris. They copiously dumped massive amounts of toxic industrial waste into the River, despite agreements made up to and including the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909. Eventually, low dissolved oxygen levels and high pollution levels in the water created an uninhabitable ecosystem. Anadromous (sea-run) fishes who were miraculously able to get past the dams died after only 24 hours in the river water. Over the years, fish passageways were built and improved, only to fall into disrepair and neglect. Newer technologies have incrementally decreased the water pollution, but the Passamaquoddy’s traditional fisheries have yet to return to levels that can sustain them.

The effort to restore the health of the Skutik River ecosystem began many years ago with the work of Brian Altvater, who founded the Schoodic RiverKeepers, a grassroots, non-political group of volunteers who work to restore the river ecosystem. At the signing Ceremony, he said “In 2002, at the Milltown dam here between Calais and St. Stephen, they counted 900 alewives. 900. If you could think about it. Last year, there were well over 600,000 fish. You think about that. That’s quite a change.” He credited this rebound in fish population to the work that Riverkeepers have done over the years since the passage of LD 72, An Act To Open the St. Croix River to River Herring in 2013, which was introduced in the Legislature by then Passamaquoddy Representative Madonna Soctomah. The bill reversed an earlier closing of fish passageways in 1995 when sport fishers and guides lobbied the Maine legislature with a mistaken theory that sea-run alewives posed a threat to a non-Native species of smallmouth bass that they considered part of their livelihood. In 1987 the fish count was 2.6 million. By 2002, only 900 alewives returned to the River due to the obstructions placed there by humans. Many Passamaquoddy people remember when the water churned with fish in the springtime, as recounted by Vice Chief Newell: “The scientists and the experts may contradict me… I was a little boy in the 60s. I remember at certain times of the year, the water looked like it was boiling, and it was because of the alewives migrating to spawning areas and back to the ocean. It was a pretty impressive observation that I made back then. Hopefully, that will happen again.” Chief Hugh Akagi from the Peskotomuhkati Nation across the River also spoke of his childhood experiences growing up with his tribe’s riverine culture, “Our families would come here for thousands of years. Children would play while their fathers speared fish; mothers tended fires and built wigwams. It was a happy place. It was a productive place. I’ve told everyone I know about the six-foot salmon we found lying on the beach below my house on Indian Point when I was only ten years old. That creature died because he tried to go home.”

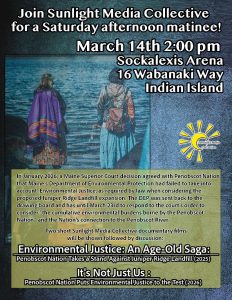

There is still much work before the tribe’s traditional and cultural fisheries can be restored, but a plan is underway. On May 26th, 2022, Passamaquoddy leadership on both sides of the River and representatives from state, federal, provincial, and Canadian government agencies signed a statement of cooperation to restore the Skutik River.

The Skutik Watershed Strategic Sea-Run Fish and River Restoration Plan is an enormous task comparable in scope to that of the work that the Penobscot River Restoration Project did. Penobscot Nation, a coalition of state and federal agencies, environmental and conservation groups, and concerned citizens partnered to restore pαnawάhpskewtəkʷ (the Penobscot River). After a 16-year dam removal process and the construction of state-of-the-art sea-run fish passageways, restoring the natural flow of parts of pαnawάhpskewtəkʷ was a resounding success, marked by the return of fish Relatives in numbers not seen in over 200 years. When the health of the Skutik River watershed is improved, fish may return to the waters of Passamaquoddy territory in numbers even higher than those counted in the Penobscot River. Brain Altvater of the Skutik Riverkeepers stated: “Estimates have put the number between 50 and 80 million fish that [could] pass up this River if it was unobstructed. And that’s what its carrying capacity is. This River has more potential than the Kennebec and the Penobscot put together.”

The same spirit of cooperation and collaboration that worked for the Penobscot River Restoration Project powers the upcoming restoration of the 95-mile-long Skutik River, with Passamaquoddy communities on both sides of the River working with the Schoodic RiverKeepers and a slate of state and federal agencies and their Canadian counterparts. The intended project will feature the removal of the Milltown Dam, built in 1881, which is the oldest dam in Canada. This river obstruction is closest to Passamaquoddy Bay and the first hurdle for fish migrating to spawn. The remaining work entails restoring stream habitats along the River and refurbishing old and inadequate fish passageways at Grand Falls and Woodland Dams. These improvements to the watershed’s natural flow will increase access to spawning areas for anadromous fish species such as Siqonomeq (alewife and blueback herring), Somelts (rainbow smelt), Skutom (sea-run brook trout), Mokahk (striped bass), Polam (salmon), Psam (shad), Kat (eel), Sakapsqetohm (sea lamprey), and Pasakos (sturgeon). Each species travels from the ocean to ancestral spawning areas in upriver streams and back (except eels, who do the opposite), and each is a vital part of the ecosystem. For example, River herring (alewives and blueback herring) are considered to be “keystone” species due to their place within the food chain as nourishment for raptors such as eagles and osprey, larger fish such as salmon, Cuspes (porpoise), and Peskotom (pollock), and as a vital nutrient source for the River.

Because state and federal governments have abrogated so many agreements with the Wabanaki people, there is cynicism as well as hope. The signing ceremony began with a prayer from Vice Chief Newell of Motahkomikuk, who later stated, “There have been many treaties, many agreements that have been broken, so it’s difficult to trust that an agreement will be implemented. So I just wanted to express a little concern about that. But with the way things have been going, and what I’ve gathered from Ed [Bassett] and Brian [Altvater], that it is very likely that this agreement will be fully implemented, and restoration of habitat and everything that needs to happen will actually happen. So that’s good news.” Representatives from government agencies said they recognized the need to honor government-to-government trust responsibilities. They voiced a commitment to a government-to-government partnership with the tribes to restore the Skutik River watershed. While the promises of government officials are reassuring, Chief Akagi of the Peskotomuhkati Tribe at Skutik accentuated the collective nature of the project, stating, “This need not be a moral promise of governments and their agencies. This [statement of cooperation] should be for all to sign, every benefactor to the territory of the Peskotomuhkati peoples and its waters, to show their commitment to the future.” Before signing the statement of cooperation, he dedicated his words to the Passamaquoddy people who have been part of the effort to restore the River over the years, specifying well-known water advocates. “I dedicate these words to Wayne Newell […] Joan Dana, Mary Bassett, Diana Francis, the Nicholas Brothers, Rita Frazier, Harold Hartford, Phyllis Hartford, Karen Hartford, and Fred McGuire.”

Tribal leadership invited people to get involved. Chief Maggie Dana of Sipayik recognized River advocates’ work over the years and voiced her appreciation and hopes for the future. “I am a RiverKeeper. And that’s all we can do is support and help as best we can. This renewed commitment, we’re connecting and partnering and building relationships. What more can you ask for? Just working together to restore this watershed and the ecosystem to help the fish. When the River flourishes, we all flourish. I hope that we’ll be able to see the results of this work in our lifetime.” Chief Akagi of Skutik issued a more plaintive plea for the River, asking, “Have we not given enough? Both the waters and my people? As greed seeks to take the last fish, the last eel, even the last tree, perhaps the last lobster, there seem to be so few who will take a stand. Who will give back? This statement tells me there are those who will.”